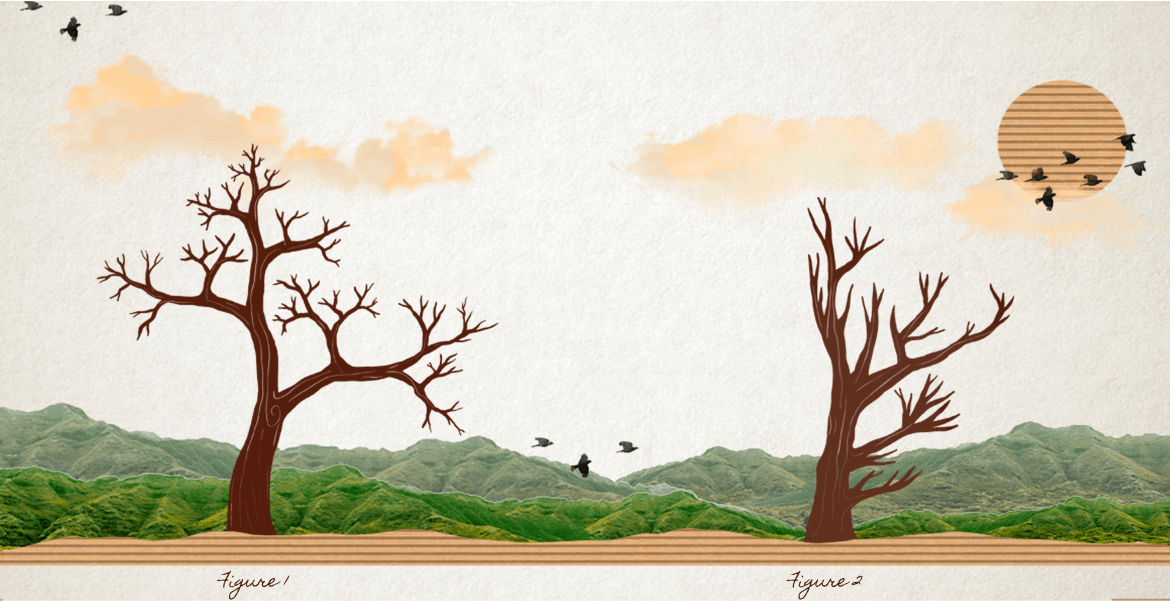

Look at the below picture. Which out of these two trees seems more inviting to you?

Compared to the right-side abomination, most of you might agree that the left tree appears to be more joyful, friendly, and less spooky. But, when they’re both made up of similar-looking branches, why do you dislike the right image so much more than the left?

The reason for this is simple: the left side tree is fractal, but the right side tree isn’t.

A fractal is a type of infinitely complex mathematical shape. In essence, a fractal is a pattern that repeats indefinitely, and every part of the fractal, no matter how zoomed in or out, appears to be identical to the entire image.

To be classified as a fractal, a shape does not have to be exactly identical. Instead, any shape that displays inherent and repeating similarities can be classified as a fractal.

Sounds pretty cool, but is this the first time you’ve heard of it? Well, it isn’t entirely new. Truth be told, we’ve been seeing fractals our entire lives—they’re all around us, and they’re at the heart of everything natural.

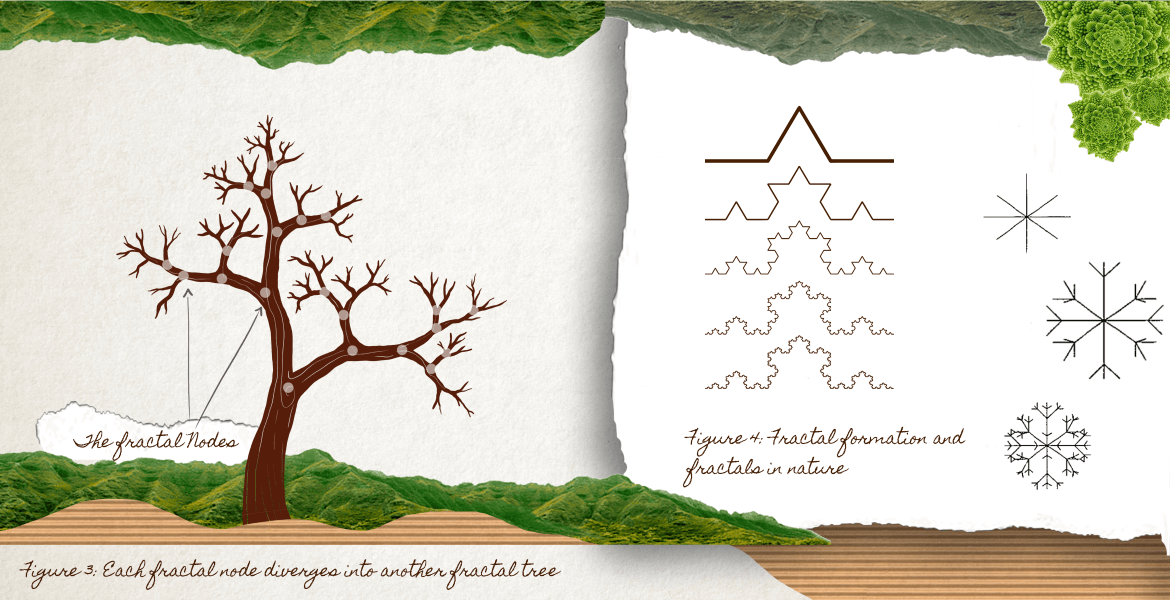

The above tree that you see is a fractal in nature that propagates by dividing each branch/path into two separate branches/paths.

The main trunk of the tree is the origin point for the fractal. Each set of branches that grow off the main trunk subsequently have their own branches that continue to grow and have branches of their own. Eventually, the branches become small enough they become twigs, and these twigs will eventually grow into bigger branches and have twigs of their own.

This cycle creates an “infinite” pattern of tree branches. So basically, each branch of the tree resembles a smaller scale version of the whole shape. Crazy right?

When thinking about fractals, some of the images that come to my mind include animal circulatory systems, snowflakes, lightning and electricity, plants and leaves, geographic terrain and river systems, clouds, crystals – honestly, the list can go on and on. There’s no doubt that these elements of fractals in nature are so beautiful, and we spend hours basking in their beauty.

So here’s a question, what if we are attracted to all the natural elements because they are fractals and not because they are organic?

Which leads us to the bigger question, “Could items not found in nature, such as paintings and architectural elements, evoke similar positive psychological and physiological responses by simply adding fractals into them?”

Let’s see how fractals fit into nature, design and architecture.

Mathematician Ron Eglash discovered numerous examples of self-similar structures in Africa, which did not only arrange dwelling units, rooms, etc. but also corresponded to the social and religious hierarchy. Furthermore, Eglash emphasized the self-similarity, not similarity between occurring fractal structures, in order to not convey a generalizing view of African vernacular architecture. (Eglash 2007)

Hindu temples in India are perhaps one of the best examples of fractal geometry in architecture that have been built long before the development of Fractal Theory.

Typically, Indian and Southeast Asian temples and monuments exhibit a fractal structure: a tower surrounded by smaller towers, surrounded by still smaller towers, and so on, for eight or more levels. Quoting William Jackson, who goes on to assert that the whole religious vision of Hinduism has a fractal character:

“This universe is like a ripe fruit appearing from the activity of the cit [consciousness]. There is a branch of a tree bearing innumerable such fruit. There is a tree having thousands of such branches. There is a forest with thousands of such trees. There is a mountainous territory having thousands of such forests. There is a territory containing thousands of such territories. There is a solar system containing thousands of such territories. There is a universe containing thousands of such solar systems. And there are many such universes contained within what is like an atom within an atom. This is what is known as cit or the subtle sun which illumines everything in the world. All the things of the world take their rise in it. Amidst all this incessant activity, the cit is ever in undisturbed repose.”

So perhaps, the fractal aspects of Hindu architecture reflect the fractal nature of Hindu cosmology.

But, today, there is a different approach to architecture – unlike the approach our ancestors took. We have transitioned to a more simplistic and minimalistic approach to designed forms, in general. But that doesn’t mean we have forgotten fractals as a whole. We have identified the key elements of what exactly makes a fractal, a fractal, and used these attributes to constitute our architectural marvels.

Above: Fig 6, Fig 7, Fig 8

Above: Fig 6, Fig 7, Fig 8 Lets read through these key attributes:

Somehow, the human brain is strangely drawn to these characteristics. Biological structures are largely fractal in their patterning, and we are innately interested in other biological structures because they might be food, or predators, or other people, or just a key component of the biologically supportive environment.

The brain has a preference for fractal structures and feels relaxed when surrounded by these. This means that one of the reasons why we like the fractals in Hindu architecture is that they remind us of our ancient, natural habitats. Because our brains have not fundamentally changed since prehistory, these biophilic responses are still at work.

However, in the modern world, the fractal forms (e.g., trees) which we crave are increasingly pushed back from our current habitats and often replaced by simple Euclidean forms. Some scholars argue that this discrepancy can lead to an increased release of stress-related hormones, which, in the long run, can have harmful effects on the human health.

Fractals are highly versatile. They aren’t just meant for mere ornamentation – they are extremely functional due to their potential to exponentially divide and branch out, and they are hence used in urban city planning. The branching, layered, fractal-like paths we can take within a city help us carry out many different tasks simultaneously. For example, If someone is traveling to a business meeting along a certain path, he/she might carry out smaller spillover exchanges with people on their way.

People moving along such paths for the purpose of higher-level information exchange (going to a business meeting) can thus carry out lower-level information exchange (having informal “spillover” exchanges with other people or perceiving pleasurable scenes). So by studying fractal structure, one can determine the most efficient system of pathways to reach the meeting and also finish up the spillover tasks effectively, saving both time and energy. Figuring out such efficient systems will translate into economic, social, and other benefits.

Another interesting aspect of fractals is the concept of fractal loading. A fractally loaded spot is a place in a pathway that has the potential to take multiple branches, leading to different activities. The fractal loading of our environment vastly expands the structural options and builds synergies between them. If one is in a well-connected, fractal-ly-loaded spot at this human scale, he/she can read the newspaper, he/she can talk to a friend, he/she can say hello to a passerby, or he/she can run one errand or more. And he/she can easily connect these activities into a web of choices. This is very likely a key reason that within urban systems, well-structured and fractally influenced pedestrian networks are so important.

The scope of using fractals to improve our lives is vast and they have the potential to better our lives in multiple ways. So the next time you say that you want to escape into the ‘beautiful chaos of nature’ to leave the order, the arrangement, and the structure of work-life…Remember that the so-called ‘chaos of nature’ is, in fact, full of order, structure and fractals.